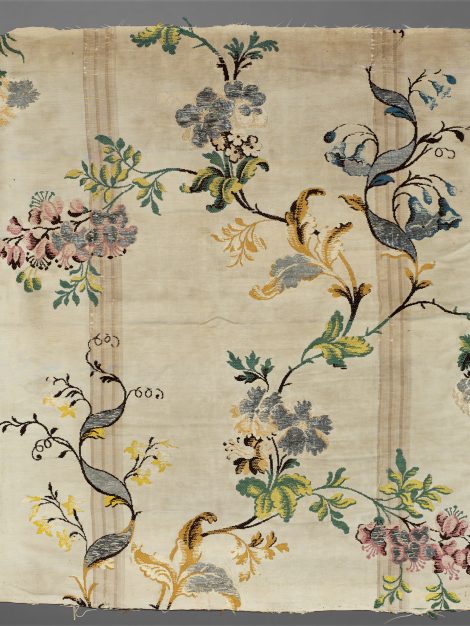

This panel, likely to have been woven in the Spitalfields district of London, the centre of the English silk industry, is a remnant of a once magnificent length of brocaded watered silk. The skills involved in the number of processes undertaken in its production and the cost of its materials would have made it a very expensive purchase. A large amount of silver thread, once bright and dazzling, has been incorporated into the design, expertly limited to the upper surface to make the most economic use of it. So precious was this thread that it was weighed both before and after the weaving process to guard against pilfering.

The continuous meandering floral designs characteristic of the early 1740s (see Related Item) have given way to these isolated sprays. Though still lively in shape, the interest in authentic botanical depiction has waned, as is evident from the more stolid flowers brocaded in limited colours, subservient to areas of metallic thread. The ground assumed greater importance, often woven with a self pattern, but here it has been watered for a similar but more random effect. The process of watering involved folding the woven silk, with the right side inwards, and putting it through the ribbed rollers of a calender under heated pressure (see a depiction of the process). The resulting effect caused light to be reflected differently on the flattened areas to create an uneven pattern. The foldline can still be seen on this piece of silk, as can the imprints of the floral motifs formed under pressure. A gown made of a very similar contemporary watered silk was worn by Lady Sarah Fermor for her portrait by Ivan Vishnyakov.

The English method of watering silk was considered superior to that of the French. In 1753 the Englishman John Badger was encouraged by the French government to establish a watering calender for the Lyon silk industry, passing on these skills to apprentices and through his brother Humphrey in Tours, which was also a centre of silk weaving.